|

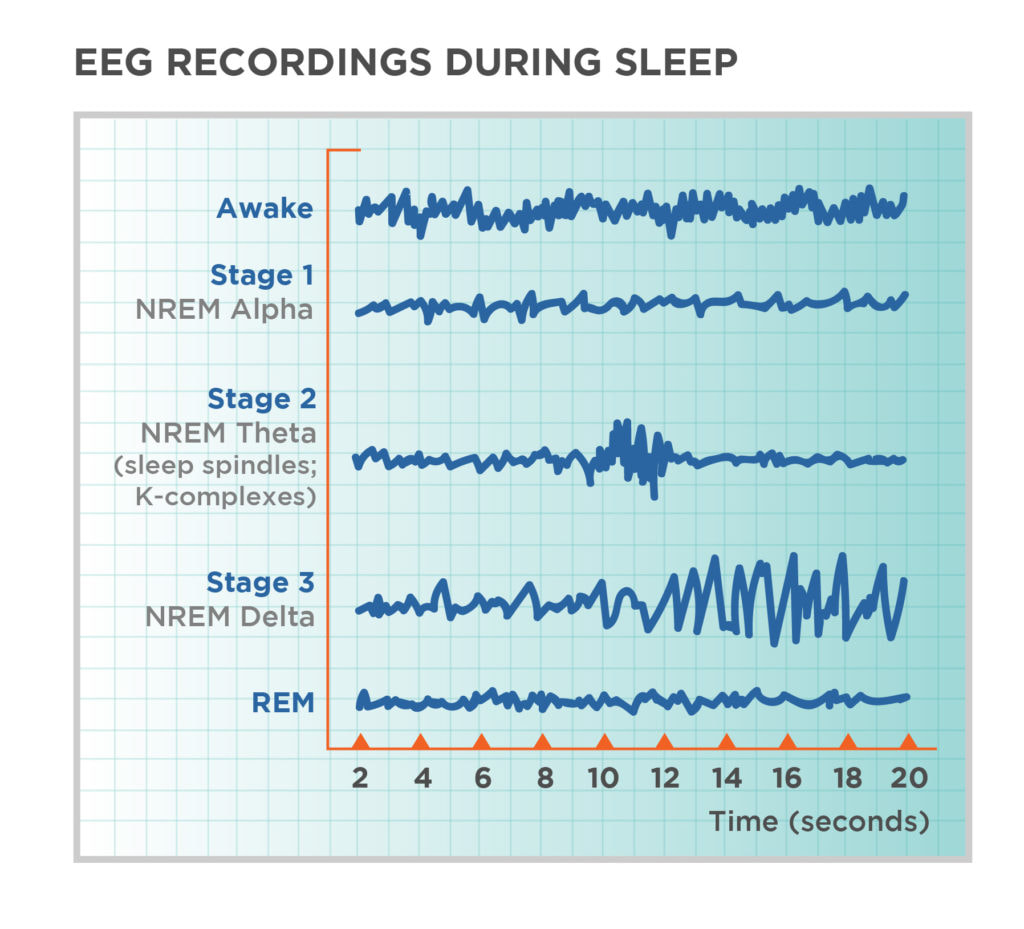

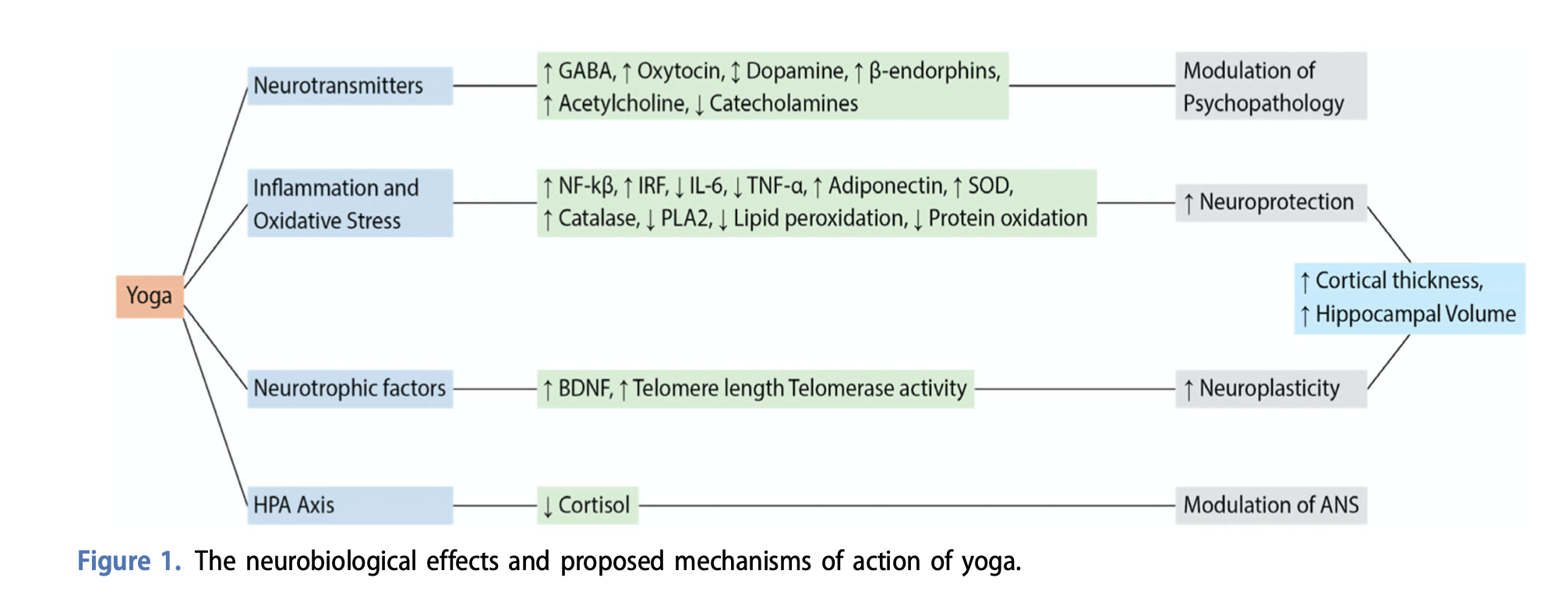

Does consciousness require brain activity? How can one sleep or rest consciously? How can yoga nidra, known as yogic sleep, offer support on a spiritual, psychological and biological level? In contemplative sleep science, there is an opportunity to map the mind. By doing this we can take known information about the psychological, neurological, physiological and biological changes observed in the scholarly literature regarding yogic sleep applicable to different aspects of wellbeing. This can assist in a more holistic model for gathering and processing data in future investigations and interventions. Thus, supporting the pursuit of attaining wellness through modalities such as yoga nidra for wellness of the whole being. Yoga nidra According to Parker et al (2013), yoga nidra is not merely relaxation, there are physiological markers differentiating this method from other relaxation modalities. As stated by Moszeik et al (2020), yoga nidra technique was developed by Swami Satyananda Saraswati in 1976 based on ancient yogic principles. According to Swami Satyananda Saraswati (1998) as cited in Parker et al (2013), yoga nidra is conscious deep sleep associated with delta waves and is deemed a super conscious meditative state called “turiya” in Sanskrit (p.14). The meditative state of turiya showed an absence of EEG brain activity, which reinforces the goal of yoga as “citta-vritti-nirodha”, translated as cessation of mental activity (Parker et al, 2014). Parker et al (2014) differentiates yoga nidra from relaxation, claiming yoga nidra to exhibit delta brain waves while relaxation alone produces alpha and theta brain waves. True yoga nidra is a conscious and deep awareness of being, which does not involve any thoughts and is conscious entry into non-REM sleep, as stated by Parker et al (2013). During this practice, one has recall and conscious awareness of their surroundings and produce alpha waves as a precursor to entering yoga nidra, which then presents by delta waves (Parker et al, 2013). The article (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017) claimed yoga nidra involves, “moving into the inner peace of the witness self at the time of sleep or rest” (p.46). Further described in (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017), the deepest level of consciousness is believed to be “dharma mega samadhi”, which is attained in true yoga nidra practice. This practice allows the practitioner to experience a free flow of knowledge while having conscious awareness in deep sleep (p.46). According to (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017), there are four meditative states in yogic practice: waking, dreaming, deep sleep and beyond with kundalini Shakti being the highest awareness. Yoga in the waking state is conscious and attentive, having ability to discern limitations of time and space. Wakefulness is having moment-to-moment mindfulness without clinging or desiring material items. According to this philosophy, individual awareness is the witness in the waking state, which is fully aware of impermanence (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017). Yoga in the dreaming state is described as conscious sleep, permitting access to the subtle elements, termed tanmantras in Sanskrit, meaning the qualities involved in the senses of sound, touch, sight, taste and smell (“Yoga in each of the four states”, 2017). As stated in (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017), “to control the mind in all states of consciousness, one must harness and discipline the senses and bring awareness into a state of uninterrupted concentration” (p.45). According to (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017), two aspects of yoga in dreaming are (1) becoming conscious in the dream state, meaning detached from the mind and body by practicing witnessing consciousness and (2) dreaming spiritual aspirations, which stimulate imagination such as in Bhakti or devotional yoga. There are two levels of yoga in deep sleep, which is characterized by formless awareness, emptiness, termed sunyata in Sanskrit, a space in which there is nothing tangible to be perceived. The first level of yoga in deep sleep (1) begins in waking state, by practicing pratyahara (sense withdrawal) by disengaging senses of external world and (2) being aware during deep sleep, beyond the mind, which (“Yoga in each of the four states,” 2017) claimed is yoga nidra truly. Kumar (2008) described yoga nidra as an altered state of consciousness. Specifically, differentiating yoga nidra as not being asleep or awake while also not in concentration or hypnosis. Singh (2010) described yoga nidra as a process in which the intellectual mind dissolves while the unconscious and subconscious mind blend into one and the concept of time and space is lost. Singh (2010) claimed rotating awareness through the body in yoga nidra technique brings about psychological effects, balancing and bringing mind-body-spirit into equilibrium for an overall calming and rejuvenating experience. Bali (2012) stated, yoga nidra is a good complementary modality in cases, which traditional psychotherapy is not adequate. Bali (2012) also indicated that yoga nidra has propensity to positively impact those suffering from anxiety. Bali (2012) described the mechanism of yoga nidra as a “profound psycho-physiological relaxation and metabolic rest” (p.24). Hoye & Reddy (2016) claimed yoga nidra is similar to hypnosis with biological markers being associated with dreamless sleep, termed “manas”, a phase of non-activity (p.118). This assertion is based on EEG brainwave readings, which showed delta brainwaves. According to Hoye & Reddy (2016), yoga nidra is finding the space between two forms of consciousness: waking (jagrata) and savanna (dream). Conscious sleep and contemplative sleep science Tart (1975) wrote that consciousness may be understood as a complex process, defined as “awareness modulated by the mind” (p.29). Thompson (2015) prompts the question regarding consciousness and if it continues in deep sleep, why could it be that sometimes individuals have trouble remembering what happens while they are asleep? Thompson (2015) highlights the perspective of yoga and Tibetan Buddhism indicating that the deepest aspects of consciousness, which are unfamiliar to normal waking consciousness are not accessible without plenty of meditation training. Thompson (2015) pointed out, the neuroscientific community mostly operates under the assumption that consciousness dwindles or stops altogether when entering deep sleep. This idea is based on the comparison between waking vs. slow-wave sleep consciousness (Thompson, 2015). Many sleep scientists correlate the inability to recall dreams or thoughts prior to waking up with the presumed absence of consciousness (Thompson, 2015, p.252). However, according to Thompson (2015), basically all cortical neurons wax and wane from active to inactive state. So what is the difference between the waking brain and the sleeping brain? According to Thompson (2015), the waking brain is active and operates by communication via many interconnected regions of the brain, recognizing patterns in the big picture. While the deep sleep brain, as Thompson (2015) claims, typically responds with quick or short-lived activity that is less broad and more localized. During slow-wave sleep there is a loss of information and communication available for integration in the brain (Thompson, 2015). Thompson (2015) differentiates phenomenal vs access consciousness in which phenomenally conscious relates to a state of felt awareness, such as in dreaming. Access consciousness is the state in which the pieces of awareness become accessible cognitively, allowing one to grasp and apply in thinking processes. Thompson (2015) stated, “yoga and Vedanta, as well as Tibetan Buddhism, also say that deep sleep consciousness can become cognitively accessible through meditative mental training” (p.257). Yogic philosophy adheres to the understanding that cognition and memory formation continues during deep sleep, while western sleep science often disagrees with this notion (p.257). In yogic philosophy, deep sleep is the place in which memories are formed from the cumulative impressions or experiences one has. An event called active memory consolidation occurs during slow-wave sleep state, which coincides with the yogic system (Thompson, 2015). In yoga nidra or sleep yoga, Thompson (2015) describes the moment as one is falling asleep as the most important moment in order to become illumined or realized in clear awareness. The space that has been mentioned in yoga nidra is described as a voidness or nothingness, as in there are no sensory inputs or tangible objects to perceive. Is it within that space that healing occurs? Gersten (1978) stated it very eloquently when he wrote, “the practitioner of yoga nidra becomes his own psychotherapist, recognizing and systematically alleviating his own personal problems and interpersonal difficulties” (p.598). Psychoneurophysiology of yoga nidra Schmidt & Walach (2014) stated, “meditative experiences and mindfulness are rooted not only in psychology, but in neuroscience and neurobiology as well”, concluding that meditation can impede stress at the “mental, physiological and molecular level” (pp.165-166). Ferreira-Vorkapic et al (2018) conducted a three month study with 60 college professors aged 30-55 years. The study participants were placed in one of three groups: 20 in yoga nidra, 20 in seated meditation and 20 in the control group. Psychological aspects observed were anxiety, depression, and stress (Ferreira-Vorkapic et al (2018). According to Ferreira-Vorkapic et al (2018), the yoga nidra intervention was effective at decreasing anxiety at a greater level than the other two groups. Both the meditation and yoga nidra groups were found to have better results overall compared to the control group. Exclusions were anyone with prior meditation experience, chronic diseases such as chronic pulmonary disease. However, those taking pharmaceuticals for diabetes, hypertension or heart disease were allowed to participate (Ferreira-Vorkapic et al, 2018). Ferreira-Vorkapic et al (2018) claim that of all the techniques for deep relaxation, yoga nidra is superior for both physical and mental health as well as preparing the mind for “yogic discipline” (p.220). Murata et al (2004) stated that meditation or having a meditative state is one in which there is deep relaxation with attention or alertness. Lou et al (1999) compared meditation to normal resting consciousness in nine adults with PET scan, measuring cerebral blood flow (CBF). Participants in this study were yoga teachers aged 23-41 years with at least five years of experience. This study helped map out different states of consciousness based upon neural connectivity. According to Lou et al (1999), differential activity were found in the following brain areas: torso-lateral, orbital frontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyri, left temporal gyri, left inferior parietal lobule, striata and thalamic regions, pons and cerebellar regions. The neural activity identified in each state of consciousness assisted in establishing and understanding of neural networks and mechanisms in the field of consciousness studies (Lou et al, 1999). Using yoga nidra as a tool for deep meditation allows the participant to act as a “neutral observer” in which the mind withdraws from wanting to act and therefore, has no emotional attachment to desires or outcomes (Lou et al, 1999, p.99). Lou et al (1999) compared global and regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) to spectral analysis of EEG, followed by analysis of subjective experience in both resting and meditative states, specifically in yoga nidra. Two hours before the PET scan, the participants practiced a technique called Tantric Kriya yoga. This method is described as practicing a detached-mind or a mind free from thoughts and worries in order to relax the mind. This study by Lou et al (1999) confirmed that the global and regional CBF could be quantified and reproduced while meditating. The meditative state showed the hippocampus and posterior sensory systems that are stimulated by using imagery rather than resting consciousness, which showed activity in the executive attention functional systems (Lou et al (1999). Kjaer et al (2002) conducted a study analyzing the regulation of conscious states at the neurophysiological level with eight healthy males aged 31-50 years with 7-26 years of meditation experience. During meditation, Kjaer et al (2002) reported findings of increased EEG activity and imagery perception during meditation as well as dopaminergic tone in several areas of the brain, which regulates the system for conscious action. According to Kjaer (2002), participants practicing yoga nidra reported vivid imagery and less attention focused on taking action. Kjaer et al (2002) suggest that conscious state meditation causes a “suppression of cortico-striatal glutametergic transmission” (p.265). This could account for the 65% increase in extracellular dopamine levels measured during this study as well as the decreased desire for action or preparing for action (Kjaer et al, 2002). Kumar (2008) conducted a study on 80 college students in which they did yoga nidra for 30 minute sessions over a six month duration. Kumar (2008) found a decrease in stress levels of both male and female college students. Kumar (2008) suggested that yoga nidra assists in coping abilities of the practitioner, reducing stress and anxiety. In a scholarly review by Bhargav et al (2021) regarding yoga, findings included reduction of cortisol levels by down regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) as well as a change in biomarkers of stress and neuroplasticity of the brain. Additionally, yoga was found to increase GABA (gamma amino-butyric acid), which increased mood and lowered anxiety (Bhargav et al, 2021). According to Bershadsky et al (2014) and Newham et al (2014) as cited in Bhargav et al (2021), yoga greatly benefited women with perinatal anxiety and depression. Bhargav et al (2021) mentioned the authors of a yoga study, which suggested the increased mood as well as increased feeling of interconnectedness and social fulfillment are due to the relationship between GABA, oxytocin and cortisol (Mehta & Gangadhar, 2019). Schmidt & Walach (2014) emphasize and support the neurobiological auto-regulatory mechanisms related to meditative states such as a rise in dopamine and melatonin levels while cortisol and norepinephrine become lower. According to Schmidt & Walach (2014), there are notable changes in structure and function in both grey and white matter of the brain, especially in areas responsible for attention, memory, interception, sensory processing and self/auto-regulation. This includes the areas of the brain responsible for managing emotions and stressors. See figure 1 below from Bhargav et al (2021) regarding the neurobiological effects and proposed mechanisms of action of yoga (p.165). Moszeik et al (2020) conducted a large heterogenous study on the effectiveness of yoga nidra for stress, sleep and wellbeing. The delivery format was an 11 minute audio recording online of guided yoga nidra meditation. Moszeik et al (2020) used Structural Equation Model (SEM) to analyze data. No prior meditation experience was required in order to participate in the study. The hope for this large and diverse study led by Moszeik et al (2020) was for participants to indicate decreased stress, decreased negative affect, increased positive affect and life satisfaction (cognitive perception of wellbeing), better sleep quality and mindfulness. Moszeik et al (2020) found decreased stress, increased scores for well-being, mindfulness and sleep quality in 341 of the participants in the meditation and yoga nidra group based on comparison of pretest, post-test (30 days between) and six weeks following the intervention.

Yoga nidra is said to regulate hyperarousal, which was addressed by the measurement tool for negative affect (Moszeik et al, 2020). The implementation of this study was economical in the online format as well as time-saving (only 11 minute yoga nidra meditation) and therefore, is plausible to replicate and reach a large number of people. The present study defined consciousness as “awareness modulated by the mind” (p.104). Participants experienced two states of consciousness: (1) resting state with normal consciousness, including control of activity, (2) meditative state with imagery, including loss of conscious control. Lou et al (1999) suggested two states of consciousness rather than awareness, claiming that consciousness is not equal to attention/awareness. However, these two aspects complement one another and based upon the study findings, Lou et al (1999) conclude that the neurocircuitry provided patterns, laying the groundwork for differentiating resting consciousness from consciousness during meditation or yoga. Neeraja & Naachimuthu (2022) conducted a study with 24 females ages 18-24 years in Kerala, India. These authors claim from their findings that short-term yoga nidra reduces stress, improves sleep quality and is considered a form of mindful meditation. The data was collected using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Participants did yoga nidra for 30 minutes per day for 21 days (3 weeks). Neeraja & Naachimuthu (2022) reported that there was a significant difference in scores for yoga nidra group when comparing pre and post test scores. Whereas, the control group was found to have no significant changes. Mohi-Ud-Din & Pandey (2018) conducted a study on 40 drug addicts, analyzing pre and post participation in a yoga nidra intervention. The authors note significant changes observed from baseline. Personality data were collected using the NFO-Five Factor Inventory assessment tool. There were changes measured in all areas including: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Mohi-Ud-Din & Pandey (2018) stated the following reflection from their study, “by developing confidence, willpower, optimism, creativity and by clearing up the unconscious repression, one can change several aspects of one’s personality through the practice of yoga nidra” (p.760). Markil et al (2012) conducted a study on heart rate variability (HRV) and yoga nidra. HRV is a measurable biomarker associated with stability of cardiac function. This measurement reveals balance or imbalance of the autonomic nervous system. Markil et al (2012) analyzed where there was a greater impact by doing yoga nidra alone or when combined with Hatha Yoga. This study included 15 women and 5 men aged 18-47 years. Both groups had significant changes in heart rate and HRV, therefore supporting that yoga helps regulate the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which is composed of the parasympathetic (PNS) rest and digest and the sympathetic (SNS) fight-or-flight systems of stress response (Markil et al, 2012). According to Markil et al (2012), the heartbeat is regulated by the balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. Heart rate variability (HRV) is measured by the intervals seen on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Markil et al (2012) elaborate further that increase parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) tone results in high HRV, which is good. While, increased sympathetic nervous system activity leads to lower HRV and thus, an electrically less stable cardiac system. This is of importance, according to Markil et al (2012) due to the increase in cardiovascular disease and death rates associated with low HRV and SNS chronic activity or overactivity. Relaxation and mind-body modalities have been studied and understood to increase Parasympathetic nervous system activity and therefore, have become an area of research interest when investigating techniques such as yoga nidra (Markil et al, 2012). Hernández et al (2016) compared 23 meditators and 23 non-meditators in a type of yoga called Sajaha yoga meditation. Data was collected using Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging as well as Voxel-Based Morphometry. Hernández et al (2016) discovered that meditators had more grey matter, mostly on the right side, than the comparison group of non-meditators. These areas of the brain, according to Hernández et al (2016), are linked to the ability to stay focused, self-regulation, compassion and the somatosensory system. This is important because Grey Matter Volume (GMV) is necessary in the processes affecting mental wellbeing, behavior, cognition and perception (Hernández et al, 2016). An area for further investigation would be to compare this type of yoga meditation with yoga nidra to understand similarities and differences. Conclusion I have explored the origin, meaning, application and outcomes on the psychoneurobiological levels of yoga nidra practice in a variety of populations. Yoga nidra as a technique does seem to be unique in that it produces delta waves or slow-wave compared to other types of meditation or relaxation techniques. One example was the study by Hernández et al (2016) mentioned, in which Sahaja Yoga meditation was observed to produce alpha and theta waves, associated with deep relaxation, but not to the level that has been measurably recorded in yoga nidra studies (delta). From this review of the literature, it seems plausible that consciousness during yoga nidra is fairly stable and controllable by the practitioner. While one does not fully fall asleep, it appears from the research reviewed that the yoga nidra practitioner can experience and reap the benefits of deep sleep on a multitude of body system functions. This is empowering to know of a technique that has been shown thus far to have favorable outcomes in the fields of psychology, neuroscience, spirituality, biology and physiology. The data on the brain changes during waking, rest and yoga nidra or yogic sleep are profound and of great interest to me personally, academically and professionally. I would like to become further informed in the expansive ways in which yoga nidra technique can be a tool to enhance wellness of the whole being in mind, body and spirit. References Bhargav, H., George, S., Varambally, S., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2021). Yoga and psychiatric disorders: a review of biomarker evidence. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(1/2), 162–169.https://doi .org.tcsedsystem.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1761087 Ferreira-Vorkapic, C., Borba-Pinheiro, C. J., Marchioro, M., & Santana, D. (2018). The Impact of Yoga Nidra and Seated Meditation on the Mental Health of College Professors. International journal of yoga, 11(3), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_57_17 Gersten, D.J. (1978). Meditation as an adjunct to medical and psychiatric treatment. American journal of psychiatry, 135(5), 598-599. Hernández, S. E., Suero, J., Barros, A., González-Mora, J. L., & Rubia, K. (2016). Increased Grey Matter Associated with Long-Term Sahaja Yoga Meditation: A Voxel-Based Morphometry Study. PloS One, 11(3), e0150757. https://doi-org.tcsedsystem.idm.oclc.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150757 Hoye, S., & Reddy, S. (2016). Yoga-nidra and hypnosis. International Journal of Health Promotion & Education, 54(3), 117–125.https://doi-org.tcsedsystem.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/14635240.2016.1142061 Kumar, K. (2008). A study on the impact on stress and anxiety through yoga nidra. Indian journal of traditional knowledge, 7(3), 405-409. Kumar, K. (2010). Psychological Changes as Related to Yoga Nidra. International Journal of Psychology: A Biopsychosocial Approach / Tarptautinis Psichologijos Zurnalas: Biopsichosocialinis Poziuris, 6, 129–137. Lou, H. C., Kjaer, T. W., Friberg, L., Wildschiodtz, G., Holm, S., & Nowak, M. (1999). A 15O-H2O PET study of meditation and the resting state of normal consciousness. Human brain mapping, 7(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:2<98::AID-HBM3>3.0.CO;2-M Markil, N., Whitehurst, M., Jacobs, P. L., & Zoeller, R. F. (2012). Yoga Nidra Relaxation Increases Heart Rate Variability and is Unaffected by a Prior Bout of Hatha Yoga. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 18(10), 953–958. https://doi-org.tcsedsystem.idm.oclc.org/10.1089/acm.2011.0331 Mehta, U. M., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2019). Yoga: Balancing the excitation-inhibition equilibrium in psychiatric disor- ders. Progress in Brain Research, 244, 387–413. https:// doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.10.024 Moszeik, E.N., von Oertzen, T. & Renner, K.H. (2020). Effectiveness of a short Yoga Nidra meditation on stress, sleep, and well-being in a large and diverse sample. Curr Psychol .https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01042-2 Mohi-Ud-Din, M., & Pandey, M. (2018). Impact of yoga nidra on the personality of drug addicts. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 9(5), 758–760. Neeraja, V. P., & Naachimuthu, K. P. (2022). Effect of Yoga Nidra on Quality of Sleep among Young Female Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 13(1), 48–52. Parker, S. Et al (2013). Defining yoga-nidra: traditional accounts, physiological research and future directions. International Journal of Yoga therapy 23(1), 11-16. Parker S. (2019). Training attention for conscious non-REM sleep: The yogic practice of yoga-nidrā and its implications for neuroscience research. Prog Brain Res. 2019;244:255-272. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.10.016. Schmidt, S., Walach, H. (2014). Meditation - neuroscientific approaches and philosophical implications: studies in neuroscience, consciousness and spirituality. Springer. Singh, G., & Singh, J. (2010). Yoga Nidra: a deep mental relaxation approach. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(S1), i71–i72. https://doi-org.tcsedsystem.idm.oclc.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.078725.238 Tart, T.C. (1975). States of consciousness. Dutton. Yoga in Each of the Four States. (2017). Hinduism Today, 39(2), 44–46.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2022

© Zen Den Yoga 2021. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this website’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Zen Den Yoga and/or the author of any website material and www.zendenyogaroseburg.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed